7. What are your plans for next quarter?

7.1 Expanding Reach Across Derbyshire

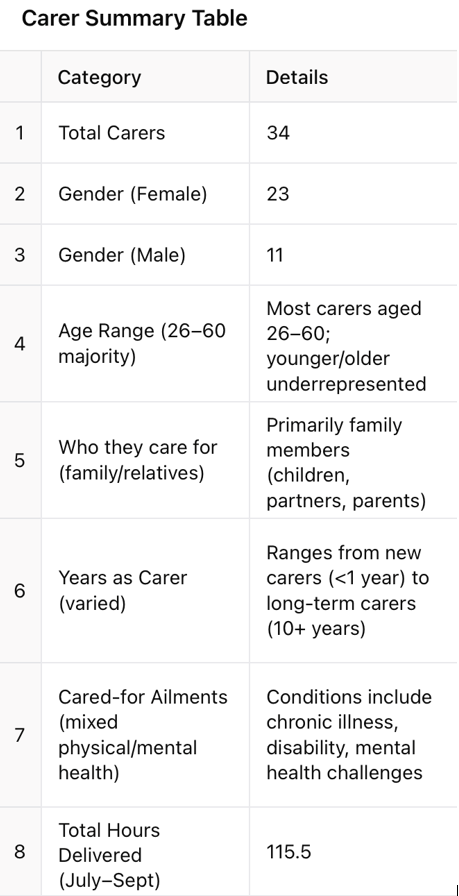

Our principal plan for Q2 is to extend the project’s reach to Carers across the whole of Derbyshire. While Q1 has engaged a committed cohort largely concentrated within Afro-Caribbean communities in Derby, we are aware of the need to diversify participation.

7.2 Reflection: Implications for the Project’s Reach

Given this ethnic landscape, several questions and possibilities emerge about how deeply the project might engage with the broader Derbyshire or even national demographic:

· If over 96% of the county’s population is White British, then the high representation of Carers from Afro-Caribbean or similar “non-White” backgrounds in the project so far is significant. It suggests the project is succeeding in reaching ethnic minorities who might otherwise be under-served or less visible in formal support systems;

· However, the small overall non-White British proportion in the county means that unless the project purposefully targets outreach in more diverse urban communities (e.g. Derby city itself, or certain wards with higher ethnic diversity), it may remain relatively “niche” in terms of representing wider ethnic diversity;

· The project’s theory of change could benefit more people if it ensures its approach (flexible, culturally sensitive, informal outreach) is responsive to the needs of minority groups, not only Afro-Caribbean Carers but also people from Asian, Mixed, Black, or “Other” backgrounds, especially in the city or more diverse parts of Derbyshire;

· Also, because national diversity is greater in many other counties or larger cities, if the project succeeds locally, it may serve as a replicable model. But this requires ensuring that the materials, methods, venues and communications are inclusive and adapted (language, culture, trust relationships) so that other ethnic groups feel the project is for them too; and

· Another question is how “self-identification as Carers” intersects with ethnicity? For example, some cultures may have different norms around defining oneself publicly as a “Carer,” which could affect participation and how the project engages.

While Derbyshire is relatively ethnically homogeneous compared to some urban areas, the project’s current engagement among non-White Carers is promising. The next quarter offers a critical opportunity to reflect on this demographic spread and to design outreach strategies that ensure the project’s benefits are accessible not just to those already reached, but to a broader and more diverse Carer population, both within Derbyshire and, potentially, beyond.

To achieve this, initially, we are organising a formal launch event, which will bring together Carers from across the county. This event will not only raise awareness but also position the project as a county-wide initiative, open and relevant to all Carers regardless of background.

The launch event will also provide an opportunity to strengthen partnerships with Carer organisations operating in different districts. By hosting future sessions within their spaces, we will be able to make the project visible and accessible in a variety of local contexts, rather than tied to a single geographic hub. This approach will ensure that Carers in rural, semi-urban, and urban areas alike have the chance to benefit.

7.3 Addressing Time as a Resource

One of the recurring challenges in Q1 has been the limited time available to the project team, who are themselves Carers. In Q2, we plan to address this by implementing clearer time allocation systems. This includes the use of digital scheduling tools, clearer division of labour, and planned blocks of time for project administration separate from therapeutic delivery.

We also plan to explore the involvement of associate practitioners and volunteers who can provide additional support. By widening the delivery team, we can relieve pressure on individual practitioners, enabling more consistent outreach and engagement. This approach will also make the project more resilient to the inevitable time pressures of caring responsibilities.

7.4 Leveraging Technology for Hybrid Delivery

Technology has already proven invaluable in Q1, with Microsoft Teams enabling participation for Carers who could not attend in person. In Q2, we intend to further refine and expand our use of digital tools. This includes:

· Developing structured online resources (templates, guides, career planning materials);

· Expanding use of hybrid sessions, where Carers can choose to attend in person or online; and

· Using digital platforms for administration, scheduling, and data collection, reducing reliance on manual recording.

By investing in technology, we aim not only to save time but also to extend accessibility, ensuring Carers in rural or underserved areas are not excluded. This will also allow us to track participation more effectively and report outcomes with greater accuracy.

7.5 Broadening the Demographic Profile of Carers

We are mindful that Quarter 1 engagement, while strong, has been demographically concentrated. In Q2, we will actively seek out partnerships with organisations supporting Carers from different communities and age groups. For example, outreach will specifically target young adult Carers (17–25) and transition parent Carers, groups underrepresented in Q1 data.

By expanding the demographic base, we will both improve inclusivity and enhance the project’s ability to demonstrate broad impact across Derbyshire’s Carer population. This will ensure the project reflects the diversity of Carers and is responsive to varied cultural, social, and professional needs.

7.6 Personal and Professional Development

We view Q2 as a time not only for expansion but also for consolidation of personal and professional growth. The challenges of Q1 prompted us to adopt new practices in time management, digital delivery, and community partnerships. In Q2, we plan to systematise these lessons, embedding them into our regular practice.

This includes structured reflection sessions for the project team, continued professional development in digital coaching tools, and ongoing evaluation of therapeutic methods. By investing in ourselves, we strengthen the capacity of the project to deliver effectively in the long term.

7.7 Summary of Q2 Plans

In summary, the next quarter will focus on:

· Hosting a formal launch event to broaden reach;

· Expanding partnerships with Carer organisations across Derbyshire;

· Addressing time pressures through structured scheduling and support;

· Enhancing hybrid delivery with new digital tools;

· Broadening demographics to engage underrepresented Carers; and

· Embedding professional growth into project practice.

These steps will ensure that Q2 builds on the successes of Q1 while addressing its limitations, enabling the project to grow in reach, inclusivity, and sustainability.